Ancient Magic in Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore and how I am trying to come to terms with JKR

I went and saw The Secrets of Dumbledore last week. I did so in a somewhat conflicted state of mind.

I strongly oppose JKR's anti-trans position, and some elements which I have seen discussed online regarding the latest Wizarding World game are unsettling to say the least. I bring this up as I had meant to occasionally address some issues of classical reception in this blog, and as an historian of ancient magic, this film definitely contains some ancient magical reception. But should I even be watching this film, let alone discussing it here? Well, my decision was influenced by a meme made out of a Tumblr post I came across a few weeks ago which addressed our interactions with problematic content and media. While me attitude might change in the future, this definitely influenced me right now:

noc10

*parts a bead curtain as i enter the room, carrying a glass of lemonade*

hey….

nothing you ever read, watch, or participate in will be ideologically pure and without its problems. your quest to consume the most unproblematic material will be, in the end, fruitless. your enjoyment of anything will be sapped away, leaving you a husk starved for media.

it is okay to enjoy things that have problems to them, so long as you do it critically and with an open mind, and take care to consider others.

*leaves the way i came*

Now, the account, noc10, is no longer active and it dates to at least December 2016, but it spoke to me with the decision to continue to watch the Fantastic Beasts films, at least for now, and it is in this spirit, acknowledging the issues of JKR's actions and some element of the Wizarding World are problematic, that I will continue to engage with this work while critically aware of this. My attitude might change later.

SPOILER ALERT: this blog will discuss elements of the film's plot.

TRIGGER WARNING: this blog will discuss elements of murder and violence.

There were a number of elements in this film where I noticed magical elements which I had looked at when researching for my recent session on dish-divining, the topic of my last blog. I can't remember exactly when in the sequence of the film that Albus Dumbledore states that Grindelwald can see "snippets" of the future, but at one point Gindelwald looks upon Albus in a pool of blood left on flagstones after he cut the throat of the young magical beast, a qilin. I think this sequence happens before Albus' revelation because my immediate thought was that the animal had been killed to enable him to magically view what Albus and his supporters were doing. I had assumed that this was an act of hydromancy using blood to spy on his enemies. This kind of magic was described by St Isidore of Seville in an extremely negative fashion:

Hydromancer are so called from water, for hydromancy is calling up the shades of demons by gazing into water, and watching their images or illusions, and hearing something from them, when they are said to consult the lower beings by use of blood.

Etymologies, 8.9.12

Isidore's view of all magic is very negative (even polemic) given his Christian background. The references to "demons" in this manner is a highly Christianised way to view such magic, and was used regardless of what medium was being used to see such images. Unfortunately, the sources I am aware of which discuss the use of blood in this manner all bring a Christian lens to this. Varro, the Roman antiquarian from the first century BCE discusses this, but we only have his description via the Christian Saint Augustine:

Varro says that this kind of divination was introduced from the Persians, and records its use by Numa himself and later by Pythagoras. He says that when blood was employed, the shades of the dead were also summoned, a practice called nekyo-mantia (νεκυομαντείαν in Greek "oracle of the dead"). But whether called hydromancy or necromancy, it is the same thing, where the dead appear to prophesy. As for the arts by which this is accomplished, I leave that to the pagans, for I will not affirm that these arts were forbidden by law in heathen cities even before the coming of our Saviour, and punished by severe penalties.The City of God Against the Pagans, 7.35

The idea of a dark wizard using blood in this manner seemed to me an apt thing for an evil wizard to do, especially using the blood of a new-born animal.

Well I was wrong. Apparently Grindelwald can just see small images of the future and we see later examples of this in the film. It has been a week since I have seen the film, so I can only sharply remember him seeing his enemies again when looking at a reflection of wet glass in a car window. This makes these visions a form of general scrying rather than specifically hydromancy. Within the Graeco-Roman understanding of hydromancy (as opposed to that of the Babylonian style), is scrying, a form of magical practice which has a long history of over 2000 years. See my previous posts here and here on that. Gazing into a crystal ball is scrying. The use of magic mirrors is also scrying. So the film is definitely tapping into this tradition.

This idea of gazing into reflective surfaces has made me think of the pensieve used by Albus Dumbledore in the original Harry Potter series. This association was not helped when I came across this miniature painting from a 12th century CE manuscript:

|

| John Scylitzes, History, Norman-Byzantine, 12th century. Biblioteca Nacional de Espana, Madrid, vitr. 26-2. Fol. 58r. |

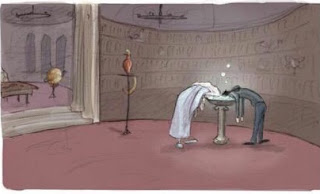

This immediately made me think of this image from a hilarious cartoon (at least to me) drawn by a talented Tumblr artist whose username is animateglee:

A pensieve reference is not out of place (although tangential) given that Grindelwald uses the spell to remove memories usually used to place them in a pensieve on a character in the film, but allows the memory to be destroyed through dissipation instead.

The second element of magic which made me think of ancient magic was the manner in which Grindelwald made the qilin he slaughtered appear to be alive. This reanimation could be called be described as necromancy, but in most ancient magic studies, necromancy refers to the use of the dead (either physically or spiritually) to tell the future or query past or present events. To some ancient Greeks and Romans, the underworld is outside of time and the spirits of the dead are huge gossips, so you raise the dead either physically or in spirit to discover what is to come to pass. For this reason, I will describe this action as reanimation, as he makes the dead creature appear to be alive again.

One example of a description of this in antiquity comes from Apuleius' novel, Metamorphoses [1.13-19]. At one point early in the book, a witch slit a man's throat and then removed his heart and replaced it with a sponge. The following morning this victim appeared to be alive and the story's protagonist doubted his own vision. The victim later drops dead of his injuries upon crossing a river. This idea of reanimating someone/thing after cutting their throat was something I could see in the Graeco-Roman past too.

The second part of Grindelwald's reanimation process made me think of Greek mythology's most well known witch, Medea. Grindelwald's carrying the dead animal into a pool of water made me think of the manner by which Medea rejuvenated a ram in Iolchis by boiling it in a pot. There are a number of different versions of this story, but the closest I know of to this is from Ovid's Metamorphoses, book seven, lines 299-321:

There, since the king himself was heavy with years, his daughters gave her hospitable reception. These girls the crafty Colchian in a short time won over by a false show of friendliness; and while she was relating among the most remarkable of her achievements the rejuvenation of Aeson, dwelling particularly on that, the daughters of Pelias were induced to hope that by skill like this their own father might be made young again. And they beg this boon, bidding her name the price, no matter how great. She made no reply for a little while and seemed to hesitate, keeping the minds of her suppliants in suspense by feigned deep meditation. When she had at length given her promise, she said to them: “That you may have the greater confidence in this boon, the oldest leader of the flock among your sheep shall become a lamb again by my drugs.” Straightway a woolly ram, worn out with untold years, was brought forward, his great horns curving round his hollow temples. When the witch cut his scrawny throat with her Thessalian knife, barely staining the weapon with his scanty blood, she plunged his carcass into a kettle of bronze, throwing in at the same time juices of great potency. These made his body shrink, burnt away his horns, and with his horns, his years. And now a thin bleating was heard from within the pot; and, even while they were wondering at the sound, out jumped a lamb and ran frisking away to find some udder to give him milk.

A pictorial rendering of a version of this story can be seen below.

|

| Attic Black Figure Hydria, featuring Medea, Pelias and his daughters. (C) British Museum, 371799001. Dating to 510-500 BCE |

While Grindelwald does not boil the qilin, his immersing a dead animal whose throat he had cut to make it appear to be alive seems to echo this idea. Though do note, in other versions of this story the ram is fully butchered into pieces. In a late description of Euripides' fragmentary play by Moses of Chlorene, it is suggested that the ram returning to life is an illusion [see page Euripides. Fragments, Edited and translated by Christopher Collard, Martin Cropp, 2008, p. 62].

Bibliography:

Apuleius. Metamorphoses (The Golden Ass), Volume I: Books 1-6. Edited and translated by J. Arthur Hanson. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996.

Augustine. City of God, Volume II: Books 4-7. Translated by William M. Green. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963.

Euripides. Fragments: Aegeus-Meleager. Edited and translated by Christopher Collard, Martin Cropp. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008

Isidore of Seville, The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Edited and translated by Stephen A. Barney, W.J. Lewis, J.A. Beach, Oliver Berghof. Cambridge: Cambridge University of Press, 2006.

Ovid. Metamorphoses, Volume I: Books 1-8. Translated by Frank Justus Miller. Revised by G. P. Goold. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1916.

Comments

Post a Comment