Meming Ancient History

I love ancient history and classics memes. I especially love the plethora of Diogenes “behold a man” memes which constantly appeared in my social media feed earlier this year, as it made me rather excited that an otherwise obscure ancient anecdote had been found and understood by the broader population. I get a similar joy from the variety of references to Ea-Nasir and his poor quality copper So I consume and share many memes, and sometimes “fact-check” them in a series of infographics which I then share out into the digital world.

I ordered a book from the library warehouse.

However, in January this year my friend Julian Barr sent me a screenshot of something he had spotted which I couldn’t address purely with an infographic; it required more research.

I ordered a book from the library warehouse.

I looked at some papers.

Then promptly got caught up in other projects.

The year is drawing to an end.

The book is being demanded back to the library.

And I am hurriedly cobbling this blog together.

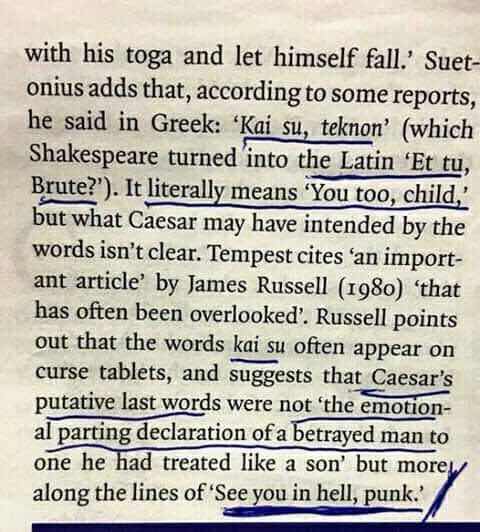

This image appears to have been shared to reddit, around three years ago. A little online sleuthing revealed that this is from the London Review of Books’ review of Katherine Tempest’s 2017 biography, Brutus: The Noble Conspirator. Thomas Jones goes so far as to entitle his review as “See you in hell, punk!”

I have not had access to this work, but I found it hard to believe that a work spoken of so well in the Bryn Mawr Classical Review would place much focus on what would be a rather small element of Brutus’ life which might never have occurred. There has been considerable doubt about whether Caesar gasped any final words. The Latin biographer Suetonius and the Greek historian Dio Cassius promote the no words version, but acknowledge that some earlier writers claimed Caesar spoke in Greek “και συ, τεκνον.” This is most commonly translated as “and you, child”, and was Shakespeare’s inspiration for “et to, Brute.” Now Suetonius was writing nearly two centuries after these events, and Dio close to three, and they had grave reservations about this story.

So the book I need to return to the library is the volume containing James Russel’s paper, “Julius Caesar’s Last Words: a reinterpretation.” This is an interesting paper in that it takes the phrase from Caesar which is commonly translated as “and you, my child”, and points out it’s similarity to the phrase και συ used apotropaically against the Evil Eye throughout the Greek speaking parts of the Mediterranean. Indeed, I illustrate the most famous example of this in my blog on the Evil Eye, a mosaic excavated in Antioch. There is another example from Rome itself where the inscription reads “και συ, έρρε” which Russel translated as “to hell with you, too.” Russel translates the line preserved in Suetonius as “to hell with you too, lad.” This is not how I would translate this, but I do agree with his final sentence:

We may never know for certain the truth of Caesar’s last words, to be sure, but we should recognize that popular tradition, right or wrong, as recorded by both Suetonius and Dio does preserve the interesting possibility that in using this apotropaic expression Caesar died with a curse on his lips.

It is a long way from “to hell with you, lad” to “see you in hell, punk.”

For this “translation” we can thank W. Jeffrey Tatum’s book Always I am Caesar. Tatum does not present this phrase as a translation of και συ. He refers to Russel’s paper and provides a different translation of και συ, ερρε (“as for you, perish!”), and finalises his discussion of it thus on page 112:

In other words, instead of whining something along the lines of “it breaks my heart, Brutus, that you, whomI have so cherished and protected, should join with these perfidious villains and deliver me into the next world,” perhaps, just perhaps,Caesar died with a curse on his lips: see you in hell, punk! Now that is a Caesar I feel more comfortable with - the indomitable scrapper who ruthlessly made himself master of Rome, and who died without a Roman son.

Tatum is not suggesting “see you in hell, punk!” as a translation, but rather as a manner to understand how και συ was potentially being used. I, like Tatum, find the idea of Caesar cursing as he was killed far more in keeping with his character. That said, I do not see that when being menaced by multiple men with daggers my first line of thought would be “gods preserve me from the Evil Eye!” While “see you in hell” might seem a more relatable response to a modern audience, that would be removing the phrase και συ from its cultural context completely; something for which I’ve seen no evidence for anywhere.

Now I know the text photographed above doesn’t say that “see you in hell, punk” is a translation, but it is really easy to think that is what is being suggested. While it didn’t get a lot of engagement on reddit, the comments give the impression that readers were blurring the lines between what was said and how it should be understood.

I do wonder how Tatum feels about his line becoming a shared image that has since also appeared on imgur, and done the occasional round on Facebook.

Personally, I translate “και συ” within the context of the Evil Eye as “back at you”, so for me Caesar’s maybe last curse was “back at you, kid / baby / beardless / milk-lip” or whatever pejorative for a young person that might come to mind.curiously, a QI - Quite Interesting post also includes my preferred reading.

My fact-check on this would be: false. Caesar might not have had any last words. If he did, he wouldn’t be preempting Dirty Harry. Did Julius Caesar die cursing his assassins, maybe. Do his reported words support this, I personally do not think so, but I might be completely wrong.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Break, Frederick E. 1999. “The καὶ σύ Stele in the FitzwilliamMuseum, Cambridge.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik vol. 126, pp. 169-74.

Jones, Thomas. 2018. “See you in hell, punk”, London Review of Books, vol. 40, no. 6.

Russel, James. 1980. “Julius Caesar’s Last Words: a reinterpretation,” in Marshall, Bruce (ed.) Vindex Humanitatis: essays in honour of John Huntley Bishop, Armidale: University of New England, pp. 123-8.

Tatum, W. Jeffrey. 2008. Always I am Caesar. Oxford: Blackwell Pub.

Ziogas, Ioannis. 2016. “Famous Last Words: Caesar’s Prophecy on the Ides of March.” Antichthon vol. 50, pp. 134-53.

Comments

Post a Comment