More on What Can be Learnt From One Papyrus, and The Problematic History of Papyrology

I sometimes find using papyrological evidence incredibly frustrating. Not because of the nature of the evidence (papyri are often fragmentary and full of holes so you expect that), but because of the way in which earlier papyrologists wrote.

The problematic nature of the study of papyri has been under greater scrutiny of late following the issues surrounding the provenance of various new fragments of papyri and questions relating to whether it is appropriate to publish papyri of questionable origin. Others have written far more and far better than I have on these topics. I would recommend reading Roberta Massa's excellent blogs on this topic as a simple starting point. She has written on this topic for over a decade, and many of the recent controversies are addressed by her. However, yesterday I had the fact that the problematic nature of papyrology has its roots in European colonialism metaphorically slap me in the face, and I thought it was worth sharing among other things.

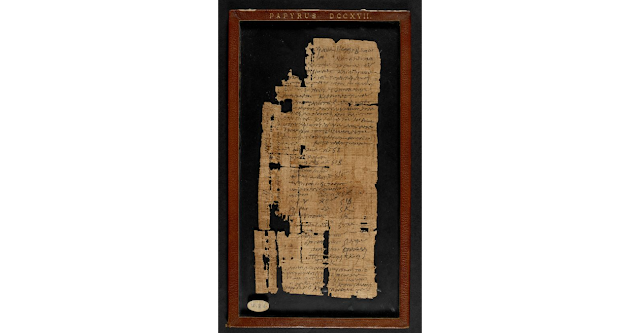

On Tuesday evening I led a discussion on of my favourite letters from Roman Egypt. It was a rather passive aggressive letter from someone who embalmed bodies giving an itemised bill to the bothers of Phibion, a deceased man, who had not arranged his funeral rites before claiming their sibling's worldly goods and leaving town. I have discussed this letter previously on this blog here (I reread this blog on Tuesday and found a number of embarrassing typos and spelling errors - whoops!) In preparation, I blew the dust off my old notes and decided to look to see if an image of this papyrus was available online. I discovered that it is part of the British Library collection, and it is indeed available to view online. Here's the photo they provide:

|

| British Library, Papyrus 717. |

It isn't the greatest quality, but it still gives us an idea.

The British Library informs us quite a bit about this letter:

Date: 260-275 CE

Title: Letter about Funeral Expenses (P.Nekr. 18, P.Grenf. II 77, Chrest. Wilck. 498, P.Lond. III 717 descr., TM 22633)

Content: A letter to Sarapion and Silvanus from Melas, who complains about their behaviour and claims some funerary expenses: instead of collecting the body of their brother Phibion, taken there by a funerary worker (nekrotaphos), and of paying for the funeral expenses, they just took the possessions of the deceased and departed. Melas lists the expenses, which amount to 520 drachmas. The docket is on the back.

Languages: Greek,

Ancient Materials: Papyrus.

Dimensions: 228 x 104 mm; housed in a glass case measuring 280 x 160 mm.

Script: Ungainly cursive hand, sloping to the right.

Ownership

Origin: Oasis Magna (El-Kharga), Western Desert, Egypt. Provenance: Kysis (Dush), Western Desert, Egypt. Purchased as part of a lot comprising Papyri 688-731 from Bernard Pyne Grenfell (b. 1869, d. 1926) on 14 November 1896.

It is worth noting that at the time that papyrologist Bernard Grenfell donated this papyrus, he was actually donating to the British Museum, not the British Library. I guess I should have been prepared to deal with a conflict of emotions given this.

Students on Tuesday asked about the context of this letter and what we knew of how and where it was found. Thanks to this entry, we knew that this letter was part of a purchased lot which meant that it was a direct result of looting of an archaeological site. Students then asked what we knew about the nature of the papyri which were bought with this letter, so we looked at a few of the Library's entries either side of this letter and saw that a number of these papyri referred to people who were nekrotaphoi. The student's had two possible interpretations for this: 1. these documents comprised of an archive from the funerary workers; or 2, this was the result of curation on the part of the sellers. I informed students that this second was highly unlikely, but that I would have a look at the papyri and get back to them regarding the nature of the collection and whether there was evidence one way or another.

As is often the case, I found yesterday that someone had indeed done this work: papyrologist Roger Bagnall. What I did find surprising was that it took someone so long to actually publish on this collection: Bagnall's study, The Undertakers of the Great Oasis (P. Nekr.), was only published in 2017. I had certainly expected it to have been done sooner on reflection. Unfortunately, this book is not in The University of Queensland library, so I am relying on book reviews for my discussion of this work.

The Problematic Academic History of my Favourite Ancient Letter

So I decided to look at Grenfell's original publication of my beloved letter and try get an understanding of the circumstances of the purchase. Grenfell published the papyri he purchased along with his colleague, Arthur Hunt, in the 1897 New Classical Fragments and Other Greek and Latin Papyri (Oxford: Clarendon Press). The description of the purchase of these papyri can be found on page 104:

This and the following ten papyri were discovered a few years ago in the Great Oasis (el Khargeh) which, though it has given us the great inscription of Tiberius Alexander, has not previously been a source of Greek papyri. From the frequent mention of the village of Kusis ... and its δημόσιον, their provenance was probably the archives of that place. ...

The find of papyri was a considerable one, but was soon scattered; some fragments were obtained at Luxor by Prof. Sayce in the winter of 1893, and published by him in the Revue des etudes grecques, 1984; they were however too incomplete to show either their origin or contents. Those published here, which are complete or nearly so, were acquired at different places during the last two years, together with a large number of fragments of varying sizes, which we withhold until we have had an opportunity of seeing those in the possession of Prof. Sayce.

Most of these papyri were probably entire when found, and only owe their present condition to the vicissitudes which they have gone through at the hands of natives. [My emphasis] It is therefore likely that fragments belonging to them have passed into other collections. The present editors would be very grateful if the owners, if there be such, of incomplete documents belonging to this find will communicate with them.

I found that bolded sentence so infuriating. This sentiment, happily published in an academic publication under the auspices of Oxford University speaks to the pervasive attitude of papyrologists, and I would say Classical scholars on the whole at this point in time. In addition to that, the cognitive dissonance of complaining about how papyri were handled by looters when the only reason they were being looted was to meet the market created by the likes of Bernard Grenfell. This passage also reeks of an attitude that Western scholars were the only people who had a right to handle this material, and that the people whose country had been taken over by European invaders were "lesser than" and not worthy to do anything with their ancestors' material culture. For me, this passage was just another example of just how much papyrology and the associated areas of study, Classics, archaeology (including Egyptology), and ancient history, have their roots deeply within European colonisation and all the uncomfortable elements associated with that.

Further Information About This Letter

Much of what I write here has come from an excellent review of Bagnall's book; that by Francisca A. J. Hoogendijk's published in 2020 and Micaela Langellotti's review from 2021. There seems to be a surprising dearth of reviews for this book. There are the only two I could find.

The Nature of the Collection

Bagnall's research has convincingly shown that this letter was one part of an archive belonging to a family of nekrotaphoi νεκροτάφοι, a term sometimes translated as "undertaker" but is better understood as "performers of the funeral rites for dead bodies." So the idea that the seller to Grenfell of looking for one Greek word and curating a series of papyri was, as I said to students, not what happened. The documents in the archive date to between 237 and 314 CE, but the majority are dated 237-261 and 283-314 CE. Part of Bagnall's argument is that one document was originally dated to 247 CE, but the archive contains a copy of this document which was made 40 years after the original date. The students queried whether or not the letter we looked at was a copy of the letter sent to the irreligious brothers, and I can now tell them that it was, and that most of the documents in this archive were in fact copies. I wonder what ancient business people would have thought about carbon paper?

Most of the people mentioned in this archive were descendants of Katamersis and of Polydeukes (aka Mersis) who was a formerly enslaved person who was freed by Katamersis' great-grandsons. These familial links would likely have also supported Bagnall's argument that this was a single archive.

As Grenfell had thought, the papyri he bought were part of a larger collection, and the additional material Bagnall adds to Grenfell's are now held in the Bodleian and Sackler Libraries in Oxford, three papyri are held by the Sorbonne University, and one is housed in the Archabbey of Beuron in Germany. That last surprised me, as it is usually associated with Latin (particularly early Christian) literature. Apparently one of these documents relates to the body of a Christian, so maybe it is this papyrus? Bagnall's work drew together 50 texts, and placed some of the fragmentary papyri from the Sackler with their "mother" documents.

The Nature of the "Undertakers"

Apparently there had previously been an idea that these nekrotaphoi had lived in the necropolis in which they worked, but the archive indicates that they owned houses and other properties, made a reasonable income, and likely belonged to the upper-middle class. Despite this, none could write, and these documents were written for them by a scribe, apparently. Bagnall makes a point that the nekrotaphoi bore names mostly derived from the deities Osiris, Isis, Khonsu, and Amun, while the scribes who were employed to write their documents mostly having Greek names. The preference for Egyptian names certainly adds to our knowledge of the cultural continuity surrounding the preparation of the dead for burial.

While the documents unfortunately do not reveal much about the actual work of nekrotaphoi, it is thought that they were responsible for mummification, providing a grave, and the accompanying rituals. What the documents do reveal is that the right to provide their services to a village was something that could be sold and purchased; one of the document describes the sale of a half-share of the right to service the village of Pmounesis and surrounding country for 300 drachmas.

The documents also indicate that these jobs were not just for men, but also for women, and that people in this profession also networked with those of the same profession in other communities.

Personal Reflections

I realise that I have differentiated between the author of this letter, Melas, as separate in his nature to the nekrotaphos he sent to transport Phibion's body. From what I have learned in the last couple of days, I should probably not differentiate between the professions of these two men. The archive also includes other examples of bodies being transported to other towns, so the transfer of human remains was not that unusual.

A student asked whether in the original letter we looked at was the body Phibion transported by a nekrotaphos owing to issues related to the potential contamination of people to be handling the dead. My immediate thought was perhaps the contamination of Phibion's body might have been a greater concern given Egyptian respect for the dead. Reading the reviews of Bagnall's work, I am now wondering if "contamination" as originally suggested might in fact play a role.

In addition to the term nekrotaphoi, a worker might also be called εξωπυλίτης exophylites which means literally "one who lives outside the gates" or αλλόφυλος allophylos which means literally "of a different race, tribe, or class." So we know that these people owed property, but these terms hints that at some time in the past there was likely to be some kind separation of these workers from the rest of the community. This origin might also explain why women within these families also worked within this profession. I also find it of interest that the archive also includes contracts for women from this family who were employed in the family trade, were also contracted to another nekrotaphos family in a different town or village to also work as a wet nurse. Employing a wet nurse from a different town seems odd; surely you could hire a local woman. Perhaps, they needed to engage a nekrotaphe to act in this role owing to some cultural requirement. The concept of contamination might explain this. I guess I need to get Bagnall's book through an inter-library loan to find out whether he addresses this question.

Bibliography

Papyrus 717, The British Library.

Comments

Post a Comment