Digital Humanities Pitfalls: not an ancient history or archaeology post

Digital humanities are being put forward as a grand new avenue for academia, including ancient history. While I love the access to sources digital humanities are making available for my personal research, I am not someone with the skills to undertake a full digital humanities project. So it comes as a surprise that I became aware of a significant problem with a digital humanities project outside of ancient history today.

They say a family which histories together stay together. Well, actually they don't, but it is true of my family. My kid brother is an historian who looks at medieval through to modern history, and my mother is our family history guru. During the current lockdown here in South East Queensland, my brother has been using records made available to Queensland State Library members to undertake some Hunt family research, and our mother has been transcribing documents he has printed up for her to put in her paper records. I act as Mum's digital assistant, looking up acronyms used in various records where they are unknown. Today, I was asked to look into what "RC" might mean which was described under "Particular Marks or Scars" in the entry for my forebear Richard Martin Case in the British Transportation Register for the ship "Mangles." The entire passage read:

Scar left eyebrow, woman inside lower right arm, RC inside left, two scars back of left thumb, scar back of left hand.

I figured this was something relating to tattoos. Yes, my convict (one of many convict forebears) great, great, great, great-grandfather was tatted up. I found this wonderful page, Convict Tattoos, devoted to convict tattoos which informed me that initials were a very common type of tattoo. "RC" literally meant "RC" tattooed on grandpa.

This page was part of The Digital Panopticon which is a Digital Transformation project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council which is a collaboration between the Universities of Liverpool, Oxford, Sheffield, Sussex, and Tasmania, and is published by the Digital Humanities Institute.

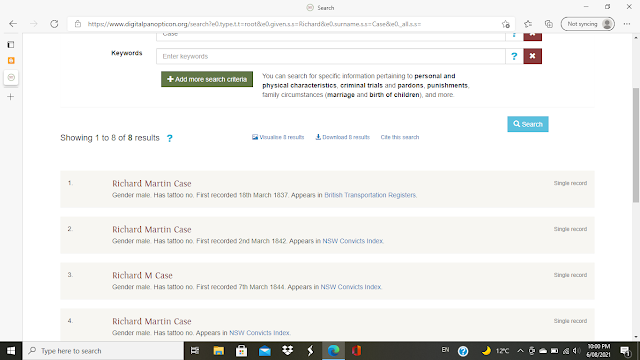

I got very excited, being someone who is in awe of those with the skills to properly interrogate data to put these kinds of projects together, and when I saw the search function at the top of the page, I immediately decided to play and see what I could find in relation to my tattooed, convict ancestor, Richard Case:

In each and every result of which there were at least five, he was described as having no tattoos. I was shocked. What was going on?

I decided to check another example from the "Mangles" register. The entrance immediately below my pick-pocketing ancestor belonged to one William Catling. He was described as having the following marks and scars:

Small mole under left jaw, heart pierced with two darts, H.C M.C B.C D.C J.C in wreath, anchor, woman, bottle, glass, and two pipes lower right arm, WC CH, man, woman, anchor, sun, H.C and heart lower left arm, three dots and scar back of left hand, small round scar left shin.

When I searched his entry, he too was described as not having a tattoo. So I looked up the record for the 42 year old seaman, James Clayton who was described as:

JACL, mermaid back of lower right arm, JC, Adam, Eve, tree and serpent, and hairy mole lower left arm, blue wristlet around each wrist, large blue illegible mark back of left thumb.

Again, when I searched the database for James Clayton on the "Mangles", the result said that the mermaid-tattooed sailor had no tattoos.

There is a significant fault in this research project. It appears that a number of the 310 male convicts sent by the ship "Mangles" to the colony of New South Wales which arrived on the 9th of July, 1837 might not have their tattoos included in this research project. This made me query how this research was conducted. I jumped around the website, looking at the description of the technical methods used included on the project's About The Project page and failed to understand much of it. I considered their points about OCR (one of the few things I understood), and thought "were they relying on the word tattoo?"

The document that I was looking at did not use the word "tattoo". I understood that the text was describing tattoo as pick-pocketing great-grandpa did not take a woman under his arm on a ship to Sydney.

And this is where digital humanities can sometimes leave us wanting.

Possibly all the tattoos of the 310 convicts on the "Mangles" might be missing from the datasets put forward within this digital humanities project. I haven't checked more than three. But regardless of the number of data points left out, all the data created from this project is now suspect to me as I know it is not as complete as the project suggests. Why? Because while digitization and using OCR is a very helpful tool, it does not provide the analysis of an historian or just a human mind. My mother and I could read that document and understand that James Clayton's mermaid was a tattoo, and thus "RC" too was a tattoo, but a computer program could not derive that "Particular Marks and Scars" could include tattoos.

I am not trying to rubbish digital humanities, and I am certainly not trying to belittle the work of the Digital Panopticon team, but we must remember that all data derived through OCR can be suspect, and no computer can replace an historian's well-trained mind. Digital humanities is only a tool, and a tool we must use carefully. If starting a research project which might require a reliance upon similar datasets, it might be worthwhile to do a few digital "test digs", mining the data in various spots and comparing it to actual documents or texts to test how reliable it is before you start.

Comments

Post a Comment