Thinking About Wet Markets - an Ancient Roman Perspective

With most of our nightly news being Covid 19 related, the peripheral clamour regarding the reopening of Wuhan’s wet market was a welcome relief from the constant reporting of case numbers, death tolls, and the latest thing extroverts were doing online to manage their mental health. While there continues to be some argument about whether this virus came out of the wet market or a neighbouring lab, the outcry from international leaders about the reopening of this market made me think about the history of such places. That said, we can place butcher’s shops in a variety of places in Rome, and all we can identify reveal something interesting. The Velabrum was mentioned by Plautus (Curculio 483), but this is extremely close to the Forum Boarium. This position would have been the easiest from which to move carcasses to a butcher’s shop, as it is adjacent. Livy (44.16.10-1) described butcher’s stalls in the proximity of the Old Shops, which had originally included butcher’s shops. This site became the location of the Basilica Semproniae next to the Forum. While not as close as the Velabrum, it is in easy walking distance of the Forum Boarium. Livy (3.48.5) also mentions a butcher’s shop among the New Shops, an area on the north side of the Forum. While it is a little further than the Old Shops, it was still within easy walking distance. So of those places in Rome where we know butchers sold their wares, we know that these shops were all within easy walking distance of the Forum Boarium, and thus it could have easily been the site at which cattle were slaughtered following their sale. I’ve marked these sites on the map in pink with a key to the right.

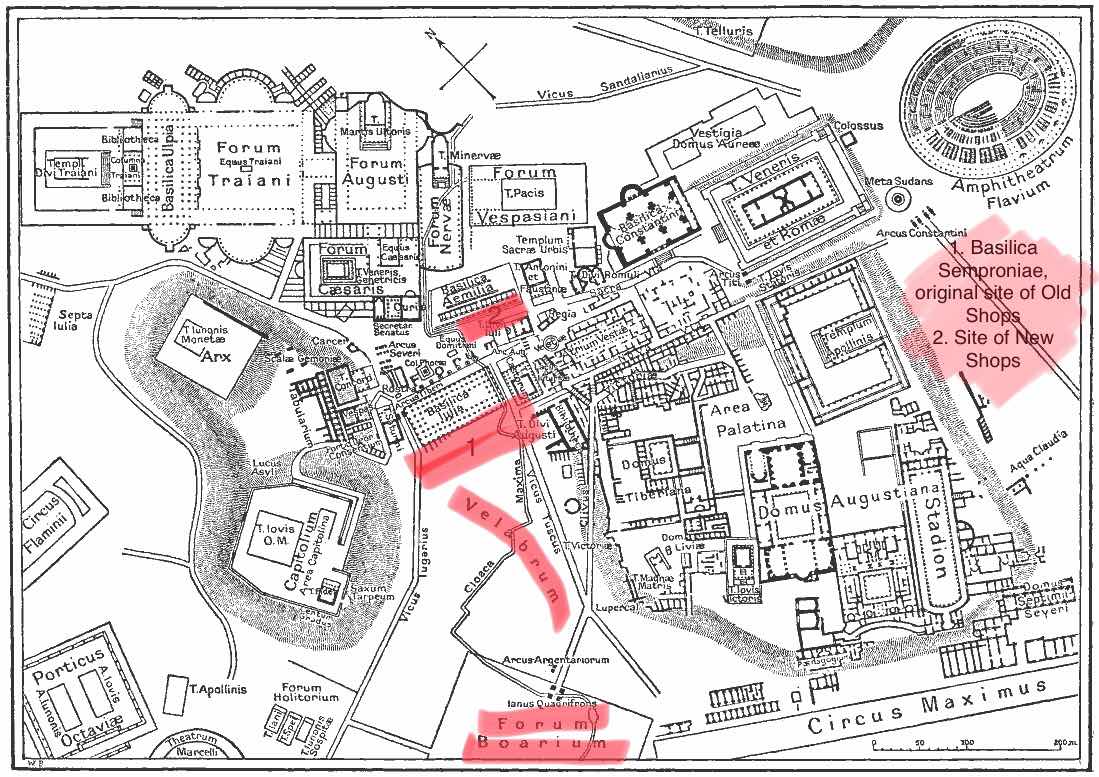

That said, we can place butcher’s shops in a variety of places in Rome, and all we can identify reveal something interesting. The Velabrum was mentioned by Plautus (Curculio 483), but this is extremely close to the Forum Boarium. This position would have been the easiest from which to move carcasses to a butcher’s shop, as it is adjacent. Livy (44.16.10-1) described butcher’s stalls in the proximity of the Old Shops, which had originally included butcher’s shops. This site became the location of the Basilica Semproniae next to the Forum. While not as close as the Velabrum, it is in easy walking distance of the Forum Boarium. Livy (3.48.5) also mentions a butcher’s shop among the New Shops, an area on the north side of the Forum. While it is a little further than the Old Shops, it was still within easy walking distance. So of those places in Rome where we know butchers sold their wares, we know that these shops were all within easy walking distance of the Forum Boarium, and thus it could have easily been the site at which cattle were slaughtered following their sale. I’ve marked these sites on the map in pink with a key to the right.

Unfortunately, these come from Republican sources, so we cannot be sure where Romans bought their meat during the Imperial period. But the best evidence for drawing comparisons between modern wet markets and those of classical antiquity comes from friezes. While butcher’s shops can be seen with hanging meat and cleavers, this marble relief from Ostia gives a far better insight. While dead birds hang in the background and fruit (possibly pears and figs) are on baskets, the table is set up on top of cages featuring possibly more birds and definitely hares. Dead animals don’t require cages. The container to the stall holder’s left might contain snails. If you look to the left of its top you can see a large snail in the background. The first customer on the left of the frieze also appears to be carrying another dead animal which appears to be some kind of short eared mammal. While Claire Holleran (see suggested further reading below) suggests that the monkeys might be entertainment to draw customers, it is worth mentioning that Phaedrus’ Fables include the story of “The Butcher and the Ape” (3.2.4 apologies for this terrible translation) in which ape meat was available for purchase. This frieze is a wet market in miniature: various fresh foods were for sale together, and small animals appear to have been kept alive until slaughtered upon sale.

But the best evidence for drawing comparisons between modern wet markets and those of classical antiquity comes from friezes. While butcher’s shops can be seen with hanging meat and cleavers, this marble relief from Ostia gives a far better insight. While dead birds hang in the background and fruit (possibly pears and figs) are on baskets, the table is set up on top of cages featuring possibly more birds and definitely hares. Dead animals don’t require cages. The container to the stall holder’s left might contain snails. If you look to the left of its top you can see a large snail in the background. The first customer on the left of the frieze also appears to be carrying another dead animal which appears to be some kind of short eared mammal. While Claire Holleran (see suggested further reading below) suggests that the monkeys might be entertainment to draw customers, it is worth mentioning that Phaedrus’ Fables include the story of “The Butcher and the Ape” (3.2.4 apologies for this terrible translation) in which ape meat was available for purchase. This frieze is a wet market in miniature: various fresh foods were for sale together, and small animals appear to have been kept alive until slaughtered upon sale.

We in western countries live in an age of refrigeration, and when living in towns and cities, we have lived for generations away from abattoirs, slaughterhouses, and to some extent, even butchers. As a result many of us are very sensitive about death, blood, and the sights and smells associated with these. I consider myself unusual for my age: I’ve seen a freshly slaughtered sheep (my mother wouldn’t allow me to watch my uncle do the deed); the cutting up of carcasses (the room where this occurred was viewable from the service area in my small town’s butchery; and I’ve smelled the appalling stench which used to be allowed to cover a town from an abattoir in the 1980s before odour regulation became a thing. In addition to this, my father carted livestock when I was a child, so I was very accustomed to the smell of animal waste. These sights and smells were common place in towns throughout history, not just ancient Rome and Greece, as well as throughout the wet markets of the world today.

Looking at meat markets in the classical world is not simple. Given that in Roman times butchers were considered a lower class of people from the perspective of Rome’s upper classes, the people whose writing we mostly rely on for sources (Cicero, De Officiis 1.42.150).

We cannot be sure exactly what butchers (laenius) did. Did they slaughter the animal, or did they just dress a carcass they purchased?

Columella (7.13) implied that butchers received lambs alive, Petronius described how a wolf had savaged sheep and let their blood “like a butcher” (Satyricon 63), and Varro (On Agriculture 2.5.11) described some finer points related to the purchase of live oxen, including to butchers. However, in addition to this, Dio Chrysostum (Discourses 77/8 “On Envy” 3) described how a butcher (μάγειρος) would buy carcasses, but this was a Greek work written during Roman times (1st to early 2nd century CE). The Greek consumption of meat was different to that of Roman society. The majority of meat became available through the sacrifice of beasts to the gods (Plutarch, Table-Talk 2.10.1; That Epicurus Actually Makes a Pleasant Life Impossible 21.1102.B), though not always (Theophrastus, Characters 9.2-4). The consumption of sacrificial meat played a partial role in Rome; Plautus described the need to bring a butcher (laenius) when preparing to sacrifice animals (Pseudolus 327-9).

In the Roman world, we know that livestock was transported to markets (Columella 7.13), and that in Rome the Forum Boarium, literally the cattle-market, was exactly that for centuries, but whether this stopped at some point is difficult to tell. We do know that this area near the round temple of Hercules by the Tiber became quite built up while it continued to act as a cattle-market, because Livy (21.62.3) described how an ox climbed to the third floor of a building in the market’s area and threw itself off in response to the building’s tenants’ sounds of alarm. Livy used the word habitator, to describe these tenants which might imply that there were residential tenements of at least three storeys height built around the cattle-market around 218 BCE; a kind of construction you will not find anywhere near an Australian salesyard today.

We do not know if the animals which were brought to the Forum Boarium were slaughtered there or elsewhere, but evidence from a Romano-British site at Wroxeter shows the cattle-market positioned right beside the market at which fresh provisions were sold, and evidence of slaughtering was found. It should also be noted that Rome’s Forum Boarium was the site of one of the city’s more grisly religious rituals: the live burial of Greeks or Celts, an act which Pliny the Elder (d. 79 CE) described as occurring in his own lifetime (Natural History 28.3.13; see also Plutarch, Marcellus 3.4). So the idea of using this area as a slaughter area might not be out of place, and would explain why flies and dogs not entering the temple of Hercules there was considered wondrous (Pliny, Natural History 10.41.79).

Unfortunately, these come from Republican sources, so we cannot be sure where Romans bought their meat during the Imperial period.

However, beef was not the only meat for sale in ancient Rome. There are also mentioned fish-markets and references to poulterers. In addition, we know that exotic animals also featured in Roman cookery, and archaeological remains from Pompeii include a butchered giraffe bone possibly as a result of eating animals hunted in the town’s amphitheatre. Exotic animals killed for entertainment were butchered and eaten in antiquity.

With areas provided within towns for multiple sellers, every town in the Roman Empire had a wet market from which all kinds of diseases might have come from. While ancient doctors were familiar with diseases coming from spoilt meat especially in summer, any number of diseases suffered in the past, and perhaps to this day, might have originated from these.

While I could never bring myself to visit a modern wet market akin to that in Wuhan, I recognise that historically these were present in the classical world with the accompanying ruckus, smell, flies, and disease.

Further Reading

I’ve tried to link to freely available sources throughout this blog and here, but some reading is behind academic paywalls the free stuff is first.

Claire Holleran, A handbook to shopping in ancient Rome https://www.historyextra.com/period/roman/a-handbook-to-shopping-in-ancient-rome/

Holleran, C. 2018. “The Retail Trade”, A Companion to the City of Rome, p. 459.

Very interesting reading Yvette,

ReplyDeleteThanks for typing it up.